Reclus 2025: What we had (already) forgotten

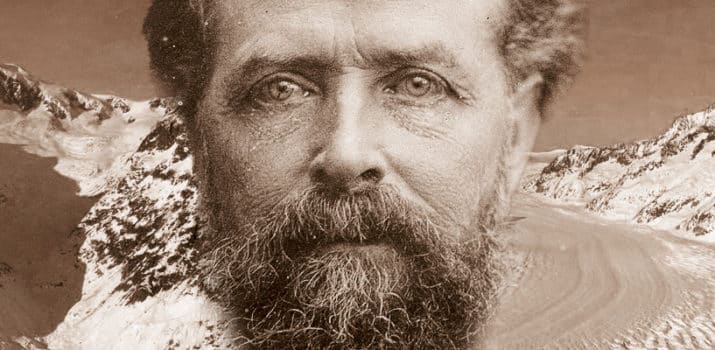

To mark the anniversary of Élisée Reclus’s death, BCUL offers a selection of documents and the following text by Christophe Mager (University of Lausanne).

Élisée Reclus died 120 years ago. And yet, at a time when university seminars on sustainability, ecological transition projects and calls for environmental justice are flourishing, we almost forget that many of the lines of his thought still resonate today. This post pays tribute to this libertarian geographer, who is all too rarely quoted, while borrowing much from him.

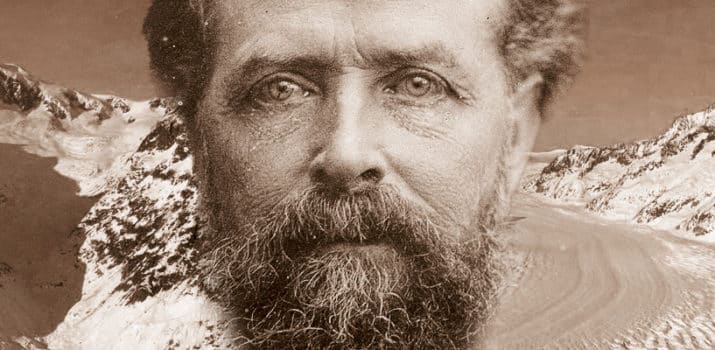

Élisée Reclus (1830-1905) wasn’t just a geographer. He was also a naturalist, an anarchist, a pacifist, an anti-colonialist, a committed vegetarian and a tireless writer. In other words, he’s hard to pigeonhole. For over thirty years, he published texts that attempted to hold together what our disciplines, institutions and agendas too often separate: nature and society, science and commitment, description and transformation, rigorous observation and poetic impulse.

When he writes that “man is nature becoming aware of itself” (L’Homme et la Terre), this is neither a vague formula nor a stylistic device. It’s a way of asserting that human societies participate fully in the dynamics of the living world, and as such, must assume their responsibility in the organization of the world. Reclus sees humans as part of the continuity of the living, and geography as a science of interrelations: between humans and environments, between techniques and forms of inhabitation, between visible landscapes and invisible structures.

This sense of connection is accompanied by a dual imperative: to understand the world is to want to make it fairer; to understand the world is not just to map or describe it, but to be accountable for its imbalances. This makes Reclus one of the few geographers of his time to combine empirical rigor, ecological awareness and social critique.

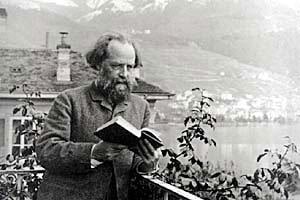

Reclus’s vision has often been summed up in his image of the “Garden Earth”. This is not a rural figure, nor an ideal of landscape tidiness, but rather an ethical and political utopia: that of a world organized according to principles of attention, care, beauty, measure and justice. What he proposes is fundamentally different from development logics based on extraction, unlimited growth and competition.

In L’Homme et la Terre, he imagines a humanity capable of transforming the planet, not to enslave it, but to inhabit it with dignity.

What’s striking on re-reading is that his work is permeated by an acute awareness of inequalities, and by the idea that these are never simply social, but also spatial. In Histoire d’un ruisseau (1869), for example, he defends the idea that social and ecological injustices are inseparable, affecting equilibrium at every scale. It’s a way of saying that domination can be seen in fragmented cities, imposed borders and unequal access to water, land and mobility. But uprisings can also be part of this.

Space can also be a source of emancipation. Alternative practices, forms of cooperation, gestures of solidarity and ways of living that sometimes escape the logic of accumulation and domination run through it. Reclus gives a detailed, and sometimes admiring, account of this.

At the University of Lausanne’sInstitute of Geography and Sustainability (IGD), few people explicitly claim to be Reclus. And yet. The words have changed, the references too, but the similarities remain.

There was a time when this link was more explicit. In the 1990s, Jean-Bernard Racine – a retired professor and pioneer of French-speaking critical geography – advised his doctoral students to read Reclus right from the start of their thesis. It was surprising. We didn’t always understand the point of going back to a 19th-century author. It was only with time that we understood its usefulness. It sometimes takes a little distance to understand that a tree, however contemporary its branches, can only flourish by relying on a living subterranean depth. Reclus’ work, sometimes forgotten, continues to fuel lines of research that sometimes believe themselves to be without genealogy.

Even today, when we work at the IGD on ecological inequalities, on a just energy transition, on the commons, on alternative forms of dwelling, on resource governance, or on participatory mapping practices, we are extending questions that he had already opened up.

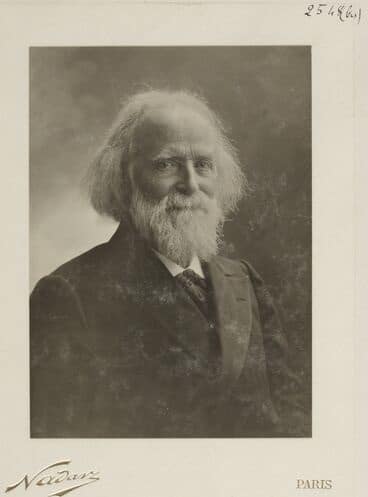

The point is not to canonize Reclus, but to note that his project for a different world, based on political, ethical and spatial principles, is still at work in geography, sometimes unwittingly.

The world of 2025 is not that of Reclus, but it’s worth returning to his texts. Admittedly, techniques have changed, ecological emergencies have worsened and forms of domination have evolved. But this does not make Reclus obsolete. On the contrary, it makes Reclus a valuable read. Not to turn it into a fixed guide, to set Reclus up as an oracle – he would have hated that – but to nourish a geographical thought that connects, that thinks at human level and on a planetary scale, that sacrifices neither rigor nor hope.

It’s also a question of form. Reclus wrote to be understood. He believed that geography should speak to everyone. At a time when publications are piling up without always finding a readership, when presentations are sometimes confined to opaque language, the demand for clarity and the pedagogical ambition that run through his work are worth a closer look.

Reclus is not a monument to be commemorated. It’s a conversation to resume.

Christophe Mager

Senior Lecturer at the Institute of Geography and Sustainability

Faculty of Geosciences and Environment, UNIL

A selection of documents is on display at the BCUL site Unithèque from June 23 to July 2. The list can also be consulted by following this link.

Listen to these podcasts to learn more about the character and his work:

Enjoy your discovery!